Popping Icons by Sarira Merikhi

By borrowing the bold iconography of Warhol and Lichtenstein to recast mythologies of Persia, Sarira Merikhi is making a new art for Iran

Illustrator and artist Sarira Merikhi makes two kinds of lithographs — the deeply sardonic and the romantically witty.

Each of her NFTs draw from references and histories found in classical Persian works, folk tales or proverbs. Some of them come from an ancient epic poem called “Shahnameh,” or “The Book of Kings,” written by a poet named Ferdowsi between 977 — 1010 CE.

Using techniques for blaring pop iconography perfected by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, Merikhi mimics the style of lithograph, a printmaking concept, by placing ancient Persian icons in settings that convey bitter truths and wry recollections of where Iran has traveled in its past. Her art, in a sense, reminds Iranians of something that nobody really has forgotten, a life and a culture that has long lived just under the surface. The popping sarcasm and witty decorativeness of her work brings it to the surface, and keeps it there.

She chats with me over the course of a couple of weeks using DMs and emails, as I get to know her art. She tells me:

What I do is combine original Iranian culture with everyday events. Because Muslim Arabs invaded Iran and Iranians converted to Islam over the years, Iranian-Islamic culture prevailed in our country and influenced our art, and it can not be separated from our culture. But the most important thing that influenced the language of the people was this book [Shahnameh], and in fact its heroes are national figures, not religious ones, like Rostam.

The history of our country and the borders of our country have always been changing, new governments have been created because of kingdoms that change every few years, but this nationalism and patriotism has always existed in Iranians.

She no longer has the illustration, but Merikhi’s artistic career began when she was five years old. She created an illustration of the Shah’s wife, a great patron of the arts and a benefactor of many museums in Iran. The illustration was chosen as the winner at an exhibition that year.

Her father is a cartoonist, and her mother is an interior designer. They nurtured her growing up with much exposure to ancient Iranian art. Both of them worked tirelessly to nurture her interest in art.

“My father had a great influence on my acquaintance with ancient Iranian art,” she says. “I can boldly say that his influence on what I do today is very great.”

Her father’s career as a cartoonist no doubt shaped her penchant for imagistic wit. It’s her satire and irony that are her most powerful assets. She says he definitely helped her absorb the history of Iranian art.

Drawing on folk symbols and images from “Shahnameh,” Merikhi usually will depict something ancient by placing it in a pop culture frame of reference, borrowing illustrative quips or making nods to artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein.

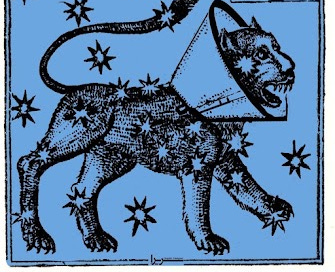

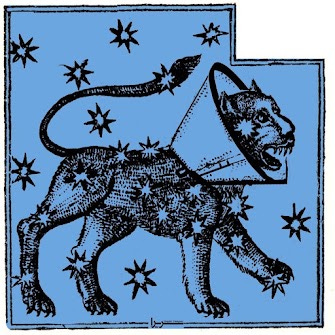

Here, the ancient lion symbol of Persia is wearing one of those collars that pets wear after they have had surgery at the vet. One might surmise that this honourable and ancient lion has been castrated, or has suffered some injury that its doctors must guard against it making worse. Hopefully, whatever wound the lion has suffered will heal.

She leans heavily on wit here, because to be more overt is to draw unwelcome scrutiny.

“Creating art and works of art in Iran is a very difficult task. Because you have to go through a lot of filters to display things. For example, as an Iranian artist, you can not openly and freely display your protest art, or you have to make the character and illustration so complex that the audience may [not] understand what you mean.”

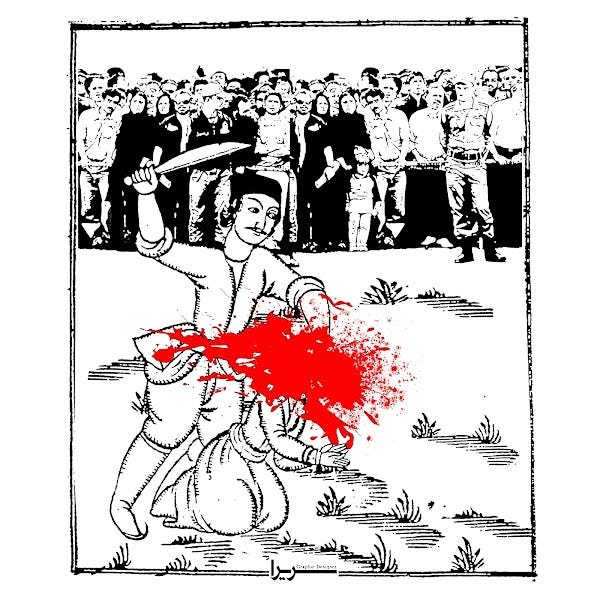

But when she pivots to being more overt in her work, Marikhi displays a jarring side of her artistic personality. She’s not afraid to take risks. Sometimes her work splashes with red blood or the red and black in it appears illuminated and stark. As bold as they are, these works typically pay respects to human loss in catastrophe, or they boldly mark events related to Iran that have a negative or even murderous outcome. All of them make a commentary on how often inhumane activity or struggle-inducing behaviour can be found in modern Iran.

Like the one above. This one is of an execution. Her summary on OpenSea says, “Execution in public, which is still happening in Iran. In this piece, I have shown that people are witnessing this horrific execution with indifference and curiosity.”

Here she is relying on a tradition in illustrative art that comes from Qajar period.

“I used this style because it has its own charm for the audience and it was very much supported by people and artists in my country,” she says. “Outside of Iran, there is usually no understanding of the Iranianization of this style because it is not as well known as it should be. And [the audience] may not even recognise the gender of the characters.”

It’s my assumption, but it’s this divide between what the West or outside of Iran knows about Iran and what Iranians know about Iran that makes her pop culture references so effective.

In this sense, she’s really telling two different stories to two different audiences, but in turn making them one story. What emerges from her work is a combination of a memorial to times gone by, a lament for some of the catastrophe and inhumanity of the present time, and a hopeful prayer to the future, that her hyper-aware and well-connected NFT fandom can piece together as many lines of the story that are possible.

Marhiki’s sense of social justice never seems to stray from the portrait. Her powerful illustrative images also share the historian’s careful eye for remembering what is often lost during the shifts of power and intrigue that rule over a country.

One of Marihki’s dreams is to design for Disney one day. This sense for history, and a deep sense of accuracy and spare, almost minimalistic eyes for detail may do her well in this regard. She has that potential.

Admittedly, it’s difficult to become an artist with an international bent in Iran. The holdings of the Tehran Contemporary Art Museum, which contain over 3,000 items of American and European contemporary art have rarely been seen. There was one exhibition in 2005, but there has not been one since.

Western art, in a sense, has taken a beating in Iran, and it is often concealed. But in a strange irony, this is actually what gives many Iranian artists their power in art. They have found an avenue in NFTs for using pop culture to drive attention for a wider more appreciative audience. But this is maybe more than just about art. This is also, in my opinion, about how one develops and experiences the joy of expanding one’s sense of self when one grows up and lives in a place that represses and controls that sense of self.

The transmission of art is the brave risk of those who wish to change, or to go beyond what they have been told they are. Merikhi’s entire range of art seems to share in this metaphoric transformation.

Like many Iranian artists who have taken to Foundation, OpenSea, SuperRare and Twitter to share their works, she is at risk when she makes critical statements about the world she lives in. But it’s this sense of sharing critical views, telling stories that cannot be repressed that establishes her not only as an artist, but as someone expanding her identity and consciousness. She ends up being an example for others — you are not what they tell you you are; you are not only one thing.

A great metaphor for this experience through art itself is found in Merikhi’s NFT “Thank You, Banksy!” In it, the lower half of a woman’s dress is shredded, in a nod to the famous Banksy portrait that sold at Sotheby’s for over 1 million Euros. At the hammer, the painting dropped through the bottom of the frame and shredded it, causing people to wonder, immediately, whether this in fact made the art more valuable.

In Merikhi’s version, a woman wearing hijab and a mask, it seems, holds a musical instrument as her lower half is shredded by the gilt frame she is held in.

Like the original Banksy, the alteration of the illustration doesn’t stand just as a comment on how art work is received and considered within systems that appraise it for its economic and cultural value.

It’s also a defence of the artist. That the artist lives on and can alter the shape of art and its reception is clear. That one takes the risk to make art, even at the risk of being mutilated or harmed, is the subtle narrative within that one.

That one is inherently valuable any time they create is still another. And probably the most important one.