Roberto Salazar and His Retraining of Ideas Through the Reduction of Forms

While in withdrawal from Benzodiazepine, Roberto Salazar found his brain was glitching. He turned to reductionism that formulated new forms as a way of creating a way out and into something timeless.

There are many spectacular answers to the philosophical question, “Why art?”

One instructive answer can be found in a reaction to this moment’s pervasiveness of information: “Because, by making new forms, we can adopt new formats of self.”

That’s meant to be more than a fancy word play. It’s my attempt to describe the philosophical structure of Mexican poet, photographer and digital artist Roberto Salazar’s art techniques.

The NFT hype wave has everyone clicking and consuming “art.” It’s led us to a world of information overload where we cannot truly take in the process and consciousness of art appreciation.

Software used for creating art on the web is rampant. Curated flows of news information have glutted our social channels with soundbites and misinformation.

Instantly available to you through free downloads, digital manipulation software helps anyone with a laptop attempt at making recognizable forms.

Perhaps it’s the absence of a standard form of beauty, a returning us to a default setting of “not knowing” that is what is needed in this moment to create the kind of idea formulation that we look to art to perform. Instead of the David statue of timeless patience and logical approaches to defeating overload, what is needed is maybe a reduction, a return to nothing. Not a nihilism, but taking a stand.

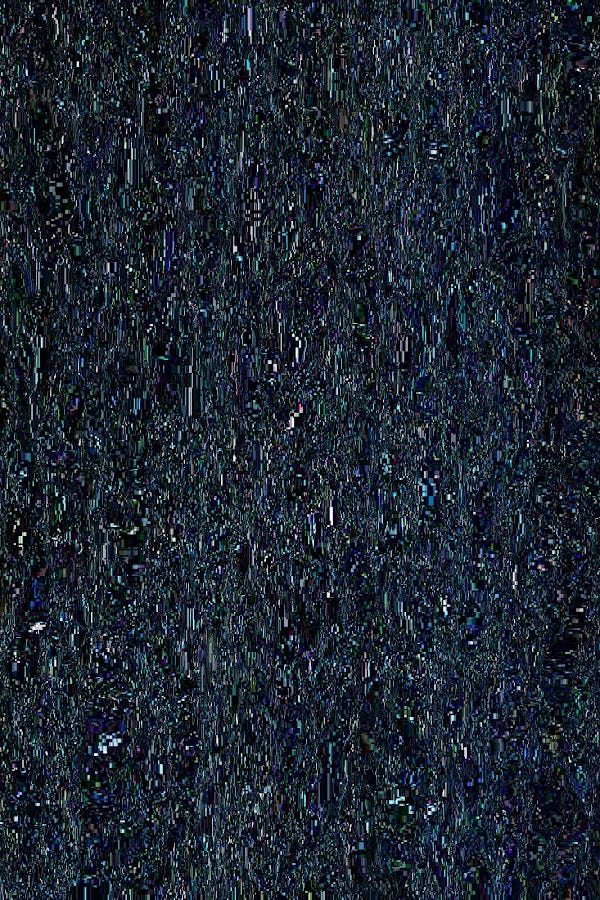

Roberto Salazar’s practice is to explode or reduce traditional forms of information. — He typically takes a pre-existing layer of media and uses software, often without fully knowing how it works, to convert sequences of bytes into a deformed new form, which gives rise to new information.

For Salazar, the sculpting of an artistic consciousness out of software and information interfacing was a mix brought on by chemical / biological withdrawal from Benzodiazepine, or tranquillisers.

Salazar lives in Monterrey, Mexico near the central plains of the country, where the Rio Santa Catarina flood plain is watched over by the looming Cerro de Silla, a mountain shaped like a saddle.

Students of American History may remember this city from the Mexican-American War. It was looted by American soldiers during that conflict, which emerged as a protest by the Mexican government and army over a recent annexation of parts of Mexico by Texas in 1845, eleven years after Texas claimed independence.

Salazar tells me that his recent digital art process began when he started to “audit” how he was using computer graphics tools and photography software. He had found himself in a state of mental disorder during withdrawal, and it had led him to wiping his hard drive, a disastrous outcome for an artist building a digital portfolio.

Salazar became very interested in how information is “curated” for our consumption. He began to think of the human mind and the human self as a kind of curation engine, one that is in constant unknowing conflict with the software algorithms that deliver us news, video, health information and more every day.

Borrowing from concepts of appropriation art, Salazar took a variety of media, like ads, and distorted them using software, not letting his “technical ignorance” of the software’s use stop him.

He found that this ignorance turned itself into a kind of tool interface of knowledge and unknowing. “The interface is the technical ignorance,” he tells me. That ignorance allows for the ability to eliminate constraints or intentions and to see what happens.

“I call this touched by fire,” he says.

Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt has said that experience in the making of art exposes his students to a different order of thinking, a consciousness where the application of an idea makes one aware of how its application takes shape. This ability to see a consciousness forming is not only a way to become more aware of the intricacy of the idea, but it’s the growth of an artistic consciousness or a way of seeing.

"What happens is that a whole set of things are articulated and released only in the making of the art," he says.

This meta-awareness is what Salazar gives form to, in my opinion.

In the “The End of Facts” series, Salazar takes old media and glitches it using digital tools, so that the interface opens itself to interpretation and then also becomes a comment itself on how information is presented.

The images go beyond being distorted, but end up much like confetti or banners of ticker tape that explode during a parade. This is entirely intentional. It’s a way of taking “information” and reducing it to something that has no power over the original creator or the audience. It results in a visual field that has no recognizable connection to the original, legacy, object.

The inspiration for this was fireworks.

In Mexico, traditional fireworks are constructed out of old newspaper. When they explode, there is literally old news and facts raining down on the crowd, says Salazar.

“You can alter what you are seeing, and it can alter how you see it,” he says of the art and the process. “I exploded them and I made a political standpoint,” he says.

Being aware of how the software algorithms we live with shape our ideologies and make our own ideologies comfortable to possess is a prime focus of Salazar’s work.

Mindlessly, we tend to be consumers in the information age, only looking at the information we are given, never processing it, deconstructing it, or trying to approach it in new ways. If we were to approach it with an artist’s mind, ergo, if we were to take up tools and apply them in making our own process for understanding, there would be a real kind of awakening or liberation, he says.

Another example of this is Salazar’s series called Pathways Limbic. Here the legacy object is a little more recognisable, but it is overpowered by the similarity of the glitch work into landscape paintings. They look more like a John Constable glade or the studio’s refraction of light captured in a Francis Bacon portrait.

Salazar has spent hours cataloging his experimentation with tools and then drafted those processes into a tool. The process is a tool. The tool and its audit sit in a set of folders on his PC desktop. It is not just the fine point of a pen or a quill, or a brush. But a method he is using. He audits the method and selects the method to articulate the new form, as best as I can work out.

By using his own “style” of the digital tool application, he is doing much more than just altering an image. In a way, he is fashioning the image into a conceptual art performance that shapes a metaphysical viewfinder for the art object. It’s also experience.

What you are seeing is almost as much a tracer of fired round as it is the trails of light you might see during an LSD trip. They may seem artificial in one’s physical experience of such things, but in an art piece it is the legacy of its making that makes it a part of the object. It makes a metaphysical sculpting into a recognisable form.

In my opinion, this is why Salazar doesn’t seem to spend much effort in ensuring there’s a reference point for the object that inspired the glitch, like you would see in other glitch artist. He wants that “tracer” of the craftmanship to remain a focus of the work.

That ends up being Salazar’s visual commentary.

This use of tools in a personalised way helps him to navigate a space where he has limited control. This limit creates a visual poetry.

“The interface is ignorance. When you have a beginner’s mind and you don’t know what the fuck you are doing, that’s a crucial point for an artist, it’s his capacity to get lost and what emerges from the technical ignorance is a voice,” he says.

The Portable Network Graphics series is another extension of this voice.

Given the prevalence of curated information on the web. Given the prevalence of readers and consumers of info on the web. Given the prevalence of free tools and software on the web, there is a high probability that a liberation of consciousness is inherent for anyone’s attempt to engage in the beginner’s encounter with the interface.

This is of course a hyperbolic statement, but the grounded truth of it should be obvious.

A consciousness of art, or for art, in inherent in the mind that engages with information or text, or any kind of medium that transmits knowledge, without forcing that interface to look a certain way.

The emergence of an art consciousness is as simple as the click of a button or a flip of a knob. An art consciousness is something as easy as smudging a watermark or even deleting a file. Or an entire hard drive.

For, it is when things are changed that their secrets are revealed.

You can find Roberto Salazar’s art on Foundation and on OpenSea.